A century ago, on August 2, 1923, President Warren Harding was lying in bed in a San Francisco hotel room recovering from what doctors suspected was a heart attack. The President had been traveling across much of the country since June in what was called a “Voyage of Understanding.” He had traveled as far as Alaska, the first President to visit America’s northernmost territory, and was making his way down the West Coast when he fell ill.

At the first sign of trouble, his personal physician, Dr. Sawyer, thought Harding had likely consumed some bad seafood, a simple case of food poisoning. A few days earlier in Seattle, after struggling to get through a speech, the President’s schedule was cleared of events in Portland and his train took him on to San Francisco for some much-needed rest.

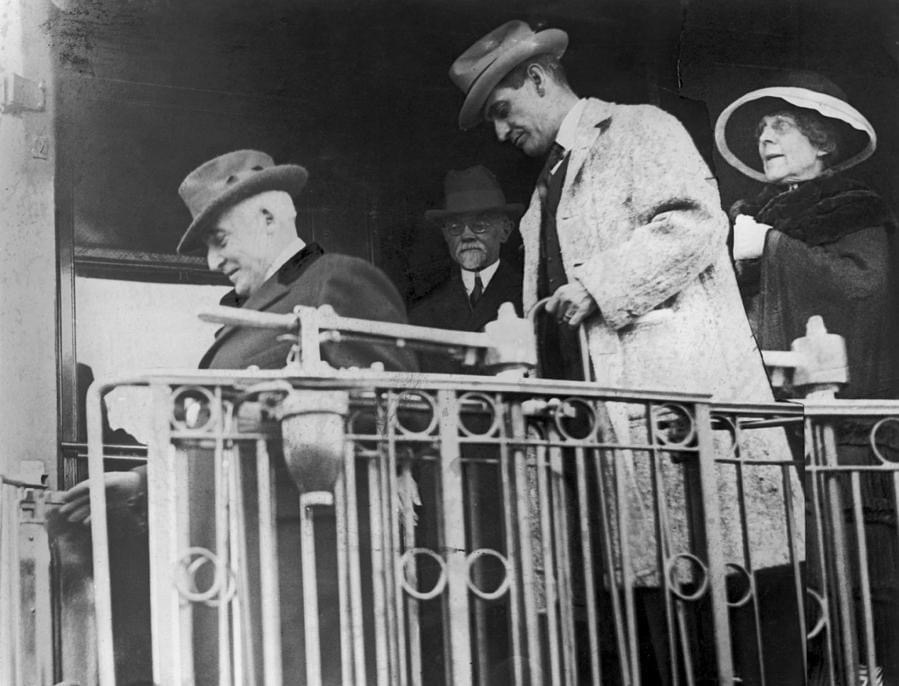

Once in San Francisco, the President checked into the Palace Hotel but doctors there, including a naval surgeon, Dr. Boone, diagnosed something much worse – a heart attack. Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover, traveling with the President, telephoned Charles Evans Hughes, the Secretary of State, and asked him to contact Vice President Calvin Coolidge. The situation seemed that bad.

But the following day Harding seemed to improve considerably. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief yet doctors wanted the President to get complete rest for the next two months. Hoover even phoned Hughes to report to him that “the worst seemed to be over.” On August 2, newspapers across the country reported that the President had weathered the worst of his illness and was on his way to recovery. But that night, while the First Lady was reading to him, President Harding died very suddenly of what most newspaper reported to be a stroke. He was fifty-seven years old.

Warren G. Harding was beloved by the nation that handed him the greatest popular vote landslide in American history up to that time, the first to gain more than 60 percent of the electorate. When the locomotive procession that took him across the country to meet and greet many of his fellow Americans was converted into a funeral train to take the fallen leader back to Washington, it was said to be the greatest outpouring of affection since Lincoln’s assassination in 1865. And eulogies praising his presidency and his personal kindness soon flooded newspapers from coast to coast.

The Commercial Appeal in Memphis wrote, “Warren Harding was a sensible, hearty, fluent man who was friendly to all. Life repaid him by being extraordinarily friendly to him,” the editors wrote. “Mr. Harding was our President. He knew no section over the other. He tried to be fair and he succeeded admirably. He was a good man.”

An editorial from the Akron Beacon Journal was entitled “Ohio’s Own Great Son.” Harding was “America’s best loved president…” He “carried into the greatest office in the world the same gentleness and simplicity that endeared him to every human being that ever met him,” the editors wrote. “He was a real man, without pretensions of any kinds. He loved his friends with a devotion that after surpassed wisdom and in his heart there was no room for animosity against enemies. Yet one’s heart rebels and even in this hour of sorrow asks whether it was the decree of fate or the foolishness of friends that has sent this great American to an untimely end.” Now, it is only time that “will fix his place in history for the rest of the world.”

“We mourn and the whole world mourns with us the passing of a gentle, kindly soul,” wrote the Los Angeles Times. “Warren G. Harding was both kind and great. He will go down into the history of this nation as one of the greatest of the Presidents. It is impossible to estimate the debt that the world owes his memory. He came to the White House at a time when the world lay bleeding in the ashes of its agony. And his voice went out to the world, calm and steady, brave and reassuring under his sane, cool, practical guidance.” Elected “in the midst of a crisis,” he “laid no claim to brilliancy. He was more than brilliant; he was great. Plain people recognized in Warren G. Harding a plain, honest, genuine, square-dealing, simple-spoken man like themselves; they knew his words and they knew him and they believed in him as few public men have been believed before. In Harding the plain virtues of common sense rose to positive genius. He had a level, sane judgment that was a pillar of strength not only to our own nation but to the world.”

These were the thoughts of those who knew the truth about our 29th President. Yet for the last 100 years, Warren Harding has been the subject of a smear campaign, tarnishing a legacy of accomplishment that is ignored by historians and unknown to most Americans.

President Harding restored the American economy from the “forgotten depression” of 1920, healed the wounds from World War I, repaired fractious relationships with foreign nations, calmed a nation in the midst of tumult, and ushered in the Roaring Twenties, the greatest period of peace and prosperity in history. He was far from a failed President.

Leave a comment